Chances are, if asked to list the 10 or 20 or 25 greatest photographers of the 20th century, few would mention Bill Brandt (1904-1983). That speaks less to the man's gifts than to his elusiveness, a quality that underlies his work and is at once its greatest strength and liability. Ultimately, it provides the thread that ties pieces together. This weekend offers a final chance to see Shadows and Substance, a collection of his work at the Akron Art Museum. At a casual glance, the 67 photos could be the work of numerous artists dedicated to the well-composed, tonally subtle black-and-white photo: They lack an obvious signature style.

The German-born Brandt began his career after a brief stint in surrealist photographer Man Ray's Paris studio in the late 1920s. Exactly how long he was there and what he did is a matter of conjecture: Brandt was often secretive or misleading about his life. Moving to London, he spent the next five decades hopscotching from subject to subject, creating bodies of work and moving on.Often, as in his images of London during the Blitz, he spent a handful of weeks on a subject, settling his attention sharply, albeit briefly. Only portraiture and the nude seemed to have held his interest consistently.

The nighttime streets of London offered the ideal launching pad for both his photojournalism career and his art. Echoing Brassa•'s contemporaneous portrayal of Paris after dark, Brandt's work has a cinematic quality. His palette of dusky gray tones gives the prints the feel of stills from a 1930s/1940s noir film. In "Footsteps" (1933), a woman's legs are visible in the upper right corner of the frame; a man strides toward her from the left. In "Soho Bedroom" (1936), a couple embraces, bed and mirror visible behind them. The shots brim with mystery and implied narrative; Brandt's love of the films of Alfred Hitchcock is clear. They also establish another quality that runs through his work: a sort of clinical detachment that seems to spring from the same source as his limited engagement with subject matter.

That sensibility extends to other sets of photos - sometimes more obviously, sometimes less. One of Brandt's most important sets of photos from the 1930s was his upstairs/downstairs-style study of poor and upper-class Londoners, which provided the material for his first book, The English at Home, published in 1936. He feels least emotionally committed here, a documentarian exploring lives that he, solidly middle-class, didn't share. Even the most effective shots, such as "Late Evening in the Kitchen" (around 1935), depicting three maids scattered around a kitchen, slumped in varying states of exhaustion, don't seem to have the complex backstories that much of his other work suggests. His "Gold Cup Day at Ascot" (1933), "A Garden Party" (around 1935) and "Drawing Room in Mayfair" (1938) have even less. They're just outstandingly elegant snapshots of an era.

Many photographers in the 1930s focused their lenses on poverty and ruin; it was in the air during the Depression. Brandt seems less enthralled with the grittiness of poverty than its visual possibilities. His 1936-1937 photos of miners and England's industrial north comprise some of his most gorgeous and melancholy work, natural subjects for the layered grays he favored at the time.Those grays mute the shots' compositional drama - the precipitous diagonal of "Coal Searchers, East Durham" (1937), the zigzag of "Man and Boy Searching for Coal on Slag Heap During Depression, Near Heworth, Tyneside" (1936) - which otherwise might seem too blatant, too virtuosic.

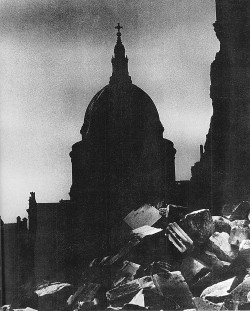

In the 1940s, Brandt turned his attention and filmic sensibility to wartime London, focusing on the war's impact on the city and its people. In "St. Paul's in the Moonlight" (around 1944), the silhouette of the famous dome pierces a cloudy night sky hovering over a pile of rubble. He photographed Londoners in bomb shelters in 1940, yet another subject he touched on briefly. After the war, heturned his attention to the countryside, undertaking a project shooting settings that inspired British authors. Like his cityscapes, these landscapes are drenched in narrative, and the author project seems an inspired match for his gifts. "Top Withens, Yorkshire Moors" (1945), with its stormy clouds and its snow-rimmed, windblown slashes of ground-hugging flora, captures vividly the bleak wildness of Emily Bront‘'s work.

Brandt's portraiture was hit-or-miss, his typical detachment not serving him especially well much of the time. But his other lifelong obsession with nudes yielded some of his most distinctive work - photographs dramatically different from the rest of his output. It was here that Brandt pushed the boundaries of traditional black-and-white photography, technically and compositionally. In the '50s, he shot with a wide-angle pinhole camera that offered a distortion and depth of field that allowed him to bring his latent surrealism to the fore with wildly canted limbs and strange juxtapositions. "Portrait of a Young Girl, Eaton Place" (1955), with a woman's head reclining in profile, dominating the foreground of a scene of buildings viewed through a window, has the dreamlike quality of a Giorgio de Chirico painting. Brandt also explored a high-key, contrasty print style, virtually drained of the grays that dominate most of his other work.

The stark blacks and whites occasionally bordered on abstraction incompositions like "Nude, Camden Hill, London" (1958), an elbow outlined by the curve of a hip reduced to basic lines and forms. Although these nudes were only a small - and atypical - part of Brandt's work, one of these ranks as his most iconic image: In "Nude #36, London" (1952), a woman's face in profile, skin bleached of texture, floats inside the crook of her bent, upraised white "V" of an arm. The cool, stark beauty of the image foretold the work of photographers like David Bailey, who turned the elusiveness and detachment of Brandt's work into a metaphor for "Swinging London" in the '60s.