After all, the same artists who took care to differentiate Zwolle and Montagnese peaches (a 1692 artist treatise gave tips on how to do this) didn't stop with verisimilitude. The sumptuous objects they freeze for our delectation are at their ripe peak: The poignancy comes from our awareness that their perfection is fragile. A new exhibit at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Still-Life Paintings From the Netherlands, 1550-1720, surveys the golden age of Dutch still life for the first time. Organizing curators Wouter Kloek, head of the department of painting at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and Alan Chong, curator of collections at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston and former associate curator of paintings at CMA, have assembled 70 works that encapsulate an era. These extraordinary paintings, in their depiction of banquets and material plenty, confirm 17th-century Dutch economic prosperity, but, more importantly, they manage the feat of hinting at the transitory nature of sensuous experience while embodying that experience in as physically vivid a way as possible.

Viewing this exhibit is like enjoying a rich meal at a garden party. Suddenly, the party is interrupted by an announcement that someone in a neighboring house just keeled over with a fatal heart attack. It's momentarily shocking, but the party goes on. If one were to stop every party because of news that something tragic has happened, it would be impossible to celebrate.

It would also be impossible to celebrate without leisure time. And leisure time is made possible with money. In modern-day America, the phrase "follow the money" is synonymous with corruption, but for the 17th-century Dutch, the phrase may well have had a more positive connotation. Still giddy from their newly acquired independence from Spain, secure in their freedom to practice their own brand of Calvinist Protestantism, and thankful for a booming economy, the Dutch spared no expense when it came to enjoying the fruits of their labor.

A work such as Floris Van Dijk's "Laid Table With Cheese and Fruit" is a hymn to worldly pleasure, and viewing it today, one can't help but feel a twinge of regret that sometimes we don't notice that wheels of cheese, grapes, apples, and pears look as good as they taste. It's revealing that realizations like this take place when confronting a painting, but don't often occur when looking at the actual object in life (or via the Polaroid one took yesterday of an amply laid dinner table). Though one tends to distrust skill that calls undue attention to itself, it is, ironically, van Dijk's supreme skill in rendering texture that gives "Laid Table" its hold on the imagination. When, as here, an artist is so intent on getting the details right and succeeds so spectacularly in his task, our attention is directed back to life and how its forms and textures are worthy of our closest attention. The artist is a virtuoso, but he doesn't pursue self-aggrandizement. He seems to be saying that life, not artifice, ought to assume center stage.

The grim reaper frequently visits these sumptuous banquets. Appearing in the form of a grinning skull or a just-snuffed-out oil lamp, he's not an unwelcome guest. He, too, has something to add to the conversation, and the still-life artists were good listeners. Alan Chong, however, warns us against making a too-facile connection between skulls and the transience of life. Such objects were collected by Dutch connoisseurs "interested in naturalia and science." Also, carvings of skulls were popular in the 17th century as "accoutrements of a scholar or intellectual." Chong argues that it is not advisable to determine the meaning of any still life by focusing on a single object that appears in it. Rather, there is a constellation of associations that arises from the way that these objects have been combined. Skulls can celebrate science or indicate veneration for scholarship. Or they can symbolize "the emptiness of worldly existence." What matters is how the artist has blended the skull with other objects and what his compositional choices might be suggesting about such blends.

Chong and Kloek, in arguing for an understanding of still lifes that focuses on the ways in which they were appreciated at the time of their creation, are engaged in a serious effort to clear away the cobwebs of "traditional" attitudes toward these works. Just as Arturo Toscanini, the famous Italian orchestral conductor, declared that "tradition is the last bad performance," these talented curators dare to reopen the subject of Dutch still lifes. In essays included in the show's copiously illustrated catalog, they persuade us that many traditional interpretations of still lifes, particularly those that see the works as moralizing vehicles, are at best incomplete, because they don't "consider the relationship of the picture as a whole, including its context and style, to its subject." There is, then, a path-breaking element to this exhibit that should not be forgotten. Not only have these curators assembled a collection of some of the finest Dutch still lifes to be found anywhere, they are encouraging us to look with new lenses. They are telling us to take in the whole work before making up our minds about what it might mean.

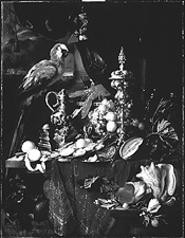

That's hard to do with paintings like Jan Davidsz de Heem's "A Richly Laid Table With Parrots." In this work, which was executed around 1655, the artist paints an extravagant table teeming with oysters, lemons, grapes, a lobster, and pomegranates. The living creatures in this work consist of a Brazilian scarlet macaw, sitting on its perch at right, and an African gray parrot on a ring at the top that blends with the rich dark olive drapery in the background. There is so much happening in such a concentrated space that one suspects that untamed extroversion is the point: At first glance, the scene is set for wealthy Dutch people to get together and enjoy a feast. The compositional subtlety suggests, however, that life is festive only after effort. The diagonal leg of a table in the foreground is echoed in the diagonal formed by the spout of the silver jug near the center. The red of the macaw's head and body is echoed in the differently textured red surface of the lobster and the crimson tablecloth. The macaw's rounded beak is echoed in the partially peeled lemon at left, a conspicuously hollow seashell at the lower right, and the leafy stem of a quartered melon just to the right of center.

The scene celebrates abundance, but it also seems to suggest that the macaw and the parrot are at home in this richly laid table in a way that humans might not be. The living creatures, reminders of nature, preside over a scene that, though bereft of human beings, nevertheless has the unmistakable stamp of human hands (who quartered the melon, peeled the lemon, and arranged the oysters on the half shell?). Whether the artist is suggesting that nature and human beings can successfully coexist, or whether he is claiming that a table like this, in its spontaneous yet carefully arranged eloquence, is redolent more of nature than of human effort (or something entirely different altogether), is not clear.

That's one of the great things about these still lifes. They are inexhaustible. The objects they focus on were well-known to 17th-century Dutch people (at least those who were well off), but the precision with which these were rendered and the resulting thematic richness is the stuff of which great art is made.

Charles Yannopoulos can be reached at [email protected].