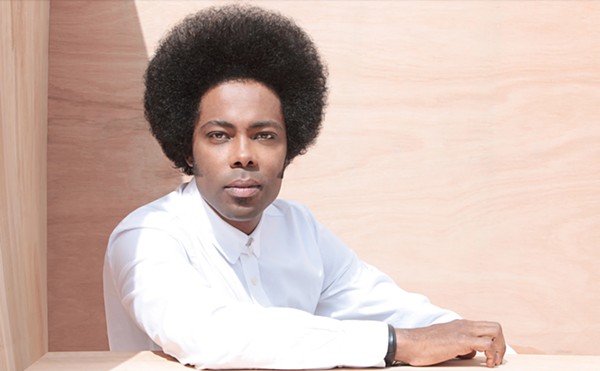

No. It's Val Kilmer.

Westerberg and Kilmer both turn forty on December 31, 1999. "Here's my plan: He and I will have dinner on the next day of the new century," Westerberg says. "That's fairly cool, to know someone who turns forty on the same day."

Worry not that Westerberg has gone Hollywood. He knows Val Kilmer as well as he knows Valerie Bertinelli, which is to say not at all. As the former frontman of the band that had one foot in the door, the other one in the gutter, Westerberg has had plenty of opportunities to exploit his brilliant, cranky, stupefying persona. "For years people have been trying to make me appear on television," he says. "I mean, I got some weird offers over the summer. They wanted me to be on Suddenly Susan as like one of her . . . I can't even remember what the fucking role was. It just baffles me why somebody thinks that's what I want to do."

There are a lot of things Paul Westerberg doesn't want to do. He says that he doesn't want to act, and that he doesn't have the patience or the skill to sit down and write a book. He's neither a nostalgist for past glories nor an astrologist for future successes. He's Paul, the drunk-turned-sober rock bastard who was too little appreciated in his twenties and too heavily scrutinized in his thirties. He walks, reads, plays with his eight-month-old son, Johnny, and feels guilty when he fritters his time.

Last week Westerberg released Suicaine Gratification, his third, fourth, first, or fourteenth record, depending on how you look at it. Officially, it's his third solo record since the Replacements disbanded in 1991. It's his fourth, if you count the in-name-only Replacements album All Shook Down, the 1990 effort on which Westerberg said screw it all to commercial pressures and the competing visions of a band that stayed together one gasp too long. It's his fourteenth, if you decide that every record on which Westerberg writes and sings is his record. And it's his first, if you feel that Suicaine Gratification represents the final stripping away of his Replacements' zoot suits, painted shoes, and elevated hair.

"It's my whatever record," Westerberg says. "If I met some old man at a bus stop, and he asked if I had a record, I'd tell him, 'Yeah, I made a record. I made a bunch of 'em.'"

Coming off his second solo tour in 1996, Westerberg felt empty. The Replacements may have split up years ago, but there he was, obliging crowds with the band's favorite non-hits. "The band disbanded, and I was sort of left with the feeling that the final stamp wasn't put on it, like I felt I still owed the fans at least a few tours to go out and play the songs we may have omitted or fucked up the last few times," he says.

"Another part of me was, I think, afraid to truly step away and be a solo artist. I mean, it was different for me; it wasn't like I said, 'I quit the band. I want to be a solo artist.' The band disintegrated around me, and I was then cast into the role of solo artist. I was still the Replacements with no band, so I kind of, you know, rode on that for a little bit, until I found that it's really no fun pretending to be a band unless you have one. It's no fun to hire guys to be in a band. Hence, I think you get my first real solo thing [on Suicaine Gratification].

When the tour was over, Westerberg turned to therapy to relieve his depression. He left Warner Bros., his home for ten years, and was ready to start over. In 1997, he released a five-song EP, Grandpaboy, on an indie label so small that even many Replacements loyalists missed it. He loved the idea of laying down some tracks, calling a buddy, and telling him to put the thing out.

That mad dash out of his system, Westerberg returned to the bigs, signing with Capitol--"a standard, we've-got-you-for-life-or-you're-gone-tomorrow" deal, he jokes. He finally felt ready to quit worrying about balancing his balladeer side with his rocker side. He would no longer carry the flag for the '80s' Greatest Rock and Roll Band That Wasn't.

Half of Suicaine Gratification was recorded at Westerberg's home in Minneapolis. The album begins with the song "It's a Wonderful Lie," which instructs the listener not to "pin your hopes or pin your dreams to misanthropes or guys like me." Part of the Replacements' magic was Westerberg's ability to slip moments of vulnerability into the band's here's-snot-in-your-eye attack. But on Suicaine Gratification, Westerberg for the first time goes out on a limb and stays there. While strumming an acoustic guitar or tapping the piano, he sings candidly about aging, beauty, ugliness, and those little black clouds that follow him everywhere. Electric guitars, when they appear, are hushed. It's exhilarating and baffling, cloying and endearing.

To make the record, Westerberg put his jester's costume in the trunk. "I always looked at my career as 'Well, if it's not fun, I'm not going to do it,'" he says. "A good deal of this music was not fun to write or make or even talk about, but I think maybe I've come to grips with what I do. It's a little more serious than what I've been allowed to do over the years."

Westerberg hasn't gone completely mushy. Suicaine Gratification has its rocking moments, suggesting his next move will not be to compose works for chamber orchestra or collaborate with Burt Bacharach. "I don't get a hell of a lot of satisfaction from the quieter stuff, and yet I'm smart enough to know their worth," he says. "It's odd, you know. A [quiet] song like 'Self-Defense,' the moment I recorded it, I knew it was special for me. I listened to it over and over again, but it's not like I wallowed in its greatness or got off on it. I surprised myself. [The harder-rocking single] 'Looking Out Forever' is more the song I listen to over and over and dig like a fan."

Ah, the fans. Westerberg says his audience didn't cross his mind when he made the record, but "I'm thinking about it now. I wasn't then, but I was certainly confused as to who they are and where they are. I sort of washed my hands of the notion that I had any [fans], and it allowed me to make this. I don't really know. I've had them of all ages. Certainly the people who came up with me when I started--my-age people--and there's people in their 70s who like what I do."

Having given up the drink, Westerberg was too coherent not to notice that his recent tours were feeling like carnivals: Come, see the original Bastard of Young! Perhaps no rock band to emerge in the post-London Calling early '80s is as hallowed as the Replacements. Every city has a story about the band coming to town and either turning a dingy club into a church of rock and roll or pissing off everyone within a three-block radius. As a solo act, Westerberg "got the feeling sometimes my fans weren't in attendance, that maybe my fans were elsewhere, but these people in the hall were looking for something they had heard from someone one day, once upon a time--which is valid, it's okay, but whether I was still capable of offering up that sort of spontaneity, I wasn't sure. You can only do it once. If they miss it, they miss it. You can't just go back and recreate it."

If they missed it, they missed a lot. When the Replacements stumbled out of Minneapolis in 1981, Westerberg, the late Bob Stinson on guitar, his younger brother Tommy on bass, and Chris Mars on drums welded the Who's rock godhead with the Sex Pistols' delinquency. They matured from the fun and dumb punk songs by their third album, Hootenanny, which featured jaw-droppers like "Within Your Reach" and "Color Me Impressed." The real breakthrough was 1985's Let It Be. While not without its flashes of idiocy, Let It Be showcased the band's dexterity with both the tough and the tender. "I Will Dare," "Unsatisfied," and "Answering Machine" powerfully documented the rage and ennui of Generation X before the term existed and Kurt Cobain could swoop in like an understudy who'd been waiting patiently in the wings.

The signing to Warner Bros. didn't diminish the band's creativity. Tim and Pleased to Meet Me were oases for rock fans turned off by hair metal and techno-pop. Don't Tell a Soul was a half-great/half-lame stab at commercial success before the whole thing fell apart with All Shook Down, an album lousy with solitude and heartache. By the end, half of the original members were gone: Self-destructive Bob Stinson was out of the band after Tim, replaced by Slim Dunlap; Stinson died in pathetic shape in 1995, his body and mind ruined by drugs and booze. Mars bolted before the All Shook Down tour.

"It was perfect in the way that it ended," Westerberg says. "We barely even mentioned it to each other. It was almost a look between Tommy and I, and we knew that it was over. We would make little comments on the bus, like 'Well, it's been nice seeing you. Laugh, laugh, laugh.' We knew it was done. He wanted to go solo. He had to get out and stretch his legs. And I knew that, once he left, the band was done. I couldn't keep Slim and call it the Replacements, so that was the end of it. Everybody thinks I went solo, and it's not really true."

The members of Kiss might have felt secure in thinking that no other band would attempt to release four solo albums simultaneously. The newly disbanded Replacements, though, virtually repeated the feat. Tommy put out the ebullient Friday Night Is Killing Me with his band Bash & Pop. Mars's Horseshoes and Hand Grenades sounded like Ray Davies gargling tar. On The Old New Me, Dunlap came across as a guy charming the roadhouse barmaid with a card trick. Westerberg made 14 Songs, which, oddly, had the least personality of the four.

The other guys presumably would have been the ones to look like Replacements gravy-trainers, but it was Westerberg who was wrestling with the group's legacy on 14 Songs and its follow-up, Eventually. Westerberg says he didn't want to go commercial in the Replacements' later years, as some of the other members did, "And then, when the band ended, I ended up trying to make more commercial music than we had."

As for the timing of the solo releases, Westerberg doesn't hold a grudge. "All of that crap is done with now," he says. "I think all the weird vibe is over with, so everything's cool, I think."

Though he felt a queer responsibility to finish what the 'Mats started, Westerberg doesn't spend a lot of time in the past, real or imagined. He told Peter Jesperson, who put out the band's early records on Twin/Tone and is working on a Replacements boxed set, to proceed with the retrospective with his blessing, but "Man, don't be calling me every day, asking me who played piano on this or whatever. I don't want to go listen to that shit. I don't want to go through the old stuff and look at the old pictures."

He adds, "I'm almost a believer that, as soon as something comes, I derive pleasure in throwing it away. It sort of frees me of it. It makes me think that you're only as good as the last thing you did, and I've always got to do something good, as opposed to having a stockpile of groovy things I've done and I can always go back to and wallow in. I'm not a saver."

Today Westerberg tries to lead as static-free a life as he can. He listens to jazz, because it allows him to think at the same time. The TV is on, but the sound is muted. "Volume bothers me," he says. "Babbling bothers me. There's shit going on in my brain all the time, and as soon as there's extraneous music or something going on, it clutters my brain."

If he's not writing or recording or taking care of his kid, he likes to read. He tries to alternate between entertaining books and deeper stuff. He's presently working through Peter Guralnick's second volume on the life of Elvis Presley, Careless Love. "I had to actually slow down, because I didn't want him to die," Westerberg says of Elvis. "It's like 'Oh, noooo.' It made me honestly feel for the first time like I could see why it could happen. I could see how that could happen to anyone. I could relate to a lot more than I thought I could. I don't know if that's just my own experience or if that's the quality of the writing. I suspect a little of both, but I know what he's feeling when he's forty years old and people want him to be something he used to be."

Westerberg is not a man who claims heroes easily. The Rolling Stones recently brought their cragged faces and Tommy wear through Minneapolis, but he didn't go to the concert. He's never seen the band live and doesn't plan to. "I have a hard time imagining me in my first rock band forty years later--no way can I relate to that."

There's always been something about Westerberg that makes one think he's going to drag all his guitars and dulcimers out to the curb for the trashman, never to play again, but fans should be encouraged by his respect for Frank Sinatra. Asked if he's ever modeled his career after someone, Westerberg hems and haws before settling on the Chairman. "You tend to look to those who have a long, varied career rather than people who tend to go up like a rocket and then burn out," he says. "I've never been a fan of those kinds of things."

It was impossible to keep Frank from performing live, even after he lost his voice and his posse had taken the big steam. But Paul? For the first time in his musician life, he doesn't have the bug to take his songs on the road. In the past, he says, he wrote with one ear toward how the song would sound live, "but I've reached the end of gearing music toward some other reason than expressing myself. It's kind of starting over again."

However, Westerberg hasn't forgotten why he got into this racket in the first place. One recent early morning, he dragged out one of his old Sex Pistols albums and played it for his baby boy. What did Johnny Westerberg think of Johnny Rotten? "He dug it, of course," Dad says. "He was sort of bopping around.