Then we find a restorative in Dobama Theatre, which last Saturday offered a series of life-enriching revelries.

In the morning was a master class taught by Keith Dinicol, a Stratford Festival acting coach, on "speaking the speech trippingly on the tongue" when doing the Bard. It was a revelation to see the look of pleasure and surprise on his face to encounter, here in Northeast Ohio, a platoon of crack Shakespeareans, of all ages and experiences, fit and able to render glorious emoting. Watching Jeannie Task's grieving queen, Lenny Pina's quicksilver gardener, and Doug Rossi's mellifluous Richard II made him wonder why our major equity companies feel compelled to order out for their Shakespearean banquets.

Dobama's mandate is to seek invigorating, locally untried scripts to keep our lives from imploding from the banality of too many game shows. Its new offering, The Trestle at Pope Lick Creek, by Naomi Wallace, is a play infinitely more arresting and graceful than its ungainly title suggests. It fills the basement theater with the sweet, intoxicating static electricity of a summer storm.

Set in Depression-era Kentucky, it is a homecoming parade of Southern Gothic, led by the ever-pervasive influence of playwright and novelist Carson McCullers. On hand is a descendant of the memorable tomboy Frankie from Member of the Wedding, and the twisted ramifications of obsessive love and desire from Reflections in a Golden Eye.

Dalton Chance and Pace Creagan are rural teenagers who seem ordained by poverty to a life of colorless tedium. They drift into an almost insane mystical relationship when they decide to break their shackles by trying to race a train across a bridge. Pace turns Dalton's indifference into an obsession worthy of D.H. Lawrence. Their strange love leads to a temporary triumph over bleak destiny. Yet, at the end, they are both overwhelmed and destroyed by their passions. In the background we have Dalton's parents, made powerless by a loss of work and identity, reduced to making shadow puppets and throwing plates out of helpless rage and frustration.

Wallace is a poet. Her play does not add up in a literal sense, yet when an alienated mother screams "Touch me!" to her dried-up husband, or when a young girl cries, "We are waiting for our lives," it elicits a lucid emotional charge. Her work is steeped in a powerful desperation.

Fred Sternfeld is a director who, up to now, has specialized in "oy-vey" comedies about meddling matchmakers and unlimited revivals of Fiddler on the Roof and its clones. He here unleashes an unseen brooding darkness that, along with Keith Nagy's smoky lighting and Ron Newell's spare set, suggests Walker Evans's photographic studies of Depression desolation. Sternfeld's direction is alternately harsh and unforgiving in the way it elucidates his characters' peccadilloes through a stance, a pout, or a grouping, yet tender in the way it shows off his young performers' verve and honesty.

A cast of old pros and two new young performers make for an evening that's implacable, centered, and majestic. In her professional debut, Jessica Swank's emotional honesty and Pre-Raphaelite, brown-eyed magnetism contribute to a performance that is more like being than acting and foretells a burgeoning stage earth mother.

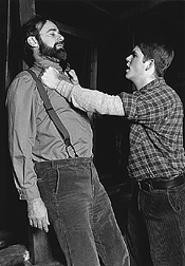

As her soulmate, 20-year-old Colin Cook has a milk-fed innocence and grace that remind one of a teddy-bear James Dean. Together, they evoke Heathcliff and Cathy in a Grant Wood Wuthering Heights. As the forlorn parents, Kirk Brown is as hauntingly hollow-eyed as a defeated bobcat, and Sheila E. Maloney, the wife who holds the family together, radiates a gospel holiness. Together they speak of Steinbeck's crushed Americana.

Some of the audience seemed to be on the verge of weeping, not out of sadness, but in awe of a haunting rural Passion Play. How exhilarating to witness a work whose generosity of spirit and depth of sympathy for human complexity is too rich to be shoved off as a disposable diversion.

Just as our grandparents lapped up bathtub gin and screamed at Sophie Tucker's bawdy innuendo, and as we, 50 years later, danced "The Time Warp" at midnight showings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, so a new generation dyes their tresses a gaudy hue and heads to Dobama's Soap Scum!, a Fox-8-like parody of soap-opera raunchiness.

For those of us well over 30, it all seems a mysterious blur, like a 3-D movie without the requisite glasses, but those for whom it was intended lapped it up with the same fervor as grandma guzzling her hootch. Each generation needs its private joke, and this, judging by all outward appearances, was an effective one, getting young people to realize that live theater need not be a school-inflicted duty but rather a pleasurable high. So tend to your knitting and send Junior.

The Trestle at Pope Lick Creek, through March 18, and Soap Scum!, through March 19, both at Dobama Theatre, 1846 Coventry Road, Cleveland Heights. 216-932-6838.

Keith A. Joseph can be reached at [email protected].