In 2015, dozens of alternative weeklies and other newsmedia outlets participated in Letters to the Future, a project published ahead of the Paris climate talks that compiled letters from nationally acclaimed writers, scientists, intellectuals and other concerned citizens. As part of the project, the letters were dispatched to hundreds of targeted delegates and citizens before they convened at the Paris sessions.

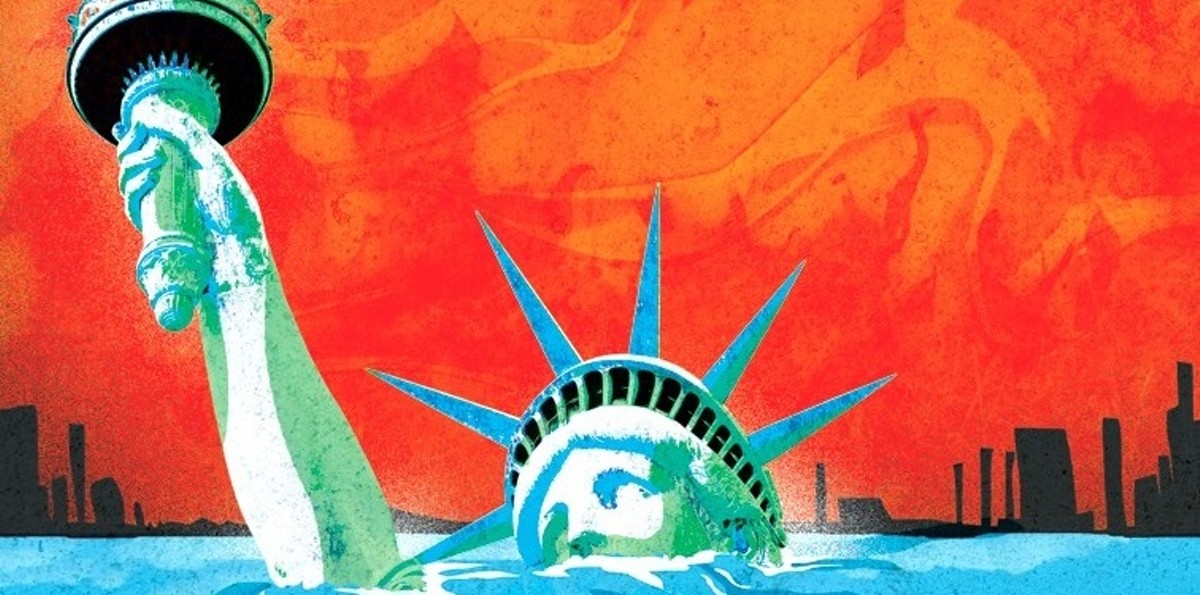

Now, with the election over, we pick up where Letters to the Future left off with a piece that examines what Donald Trump's administration could mean for climate change — and a call-to-action list for what must come next. If President-elect Donald Trump actually believes all the warnings he issued during the election about the threats of immigration, he should be talking about ways to slow global warming as well. Rising sea level, caused by the melting of the Antarctic and Greenland ice caps, will probably displace tens of millions of people in the decades ahead, and many may come to North America as refugees.

Climate change will cause a suite of other problems for future generations to tackle, and it's arguably the most pressing issue of our time. A year ago December, world leaders gathered in Paris to discuss strategies for curbing greenhouse gas emissions, and scientists at every corner of the globe confirm that humans are facing a crisis. However, climate change is being nearly ignored by American politicians and lawmakers. It was not discussed in depth at all during this past election cycle's televised presidential debates. And, when climate change does break the surface of public discussion, it polarizes Americans like almost no other political issue. Some conservatives, including Trump, still deny there's even a problem.

"We are in this bizarre political state in which most of the Republican Party still thinks it has to pretend that climate change is not real," said Jonathan F.P. Rose, a New York City developer and author of The Well-Tempered City, which explores in part how low-cost green development can mitigate the impacts of rising global temperatures and changing weather patterns.

Rose says progress cannot be made in drafting effective climate strategies until national leaders agree there's an issue.

"We have such strong scientific evidence," he said. "We can disagree on how we're going to solve the problems, but I would hope we could move toward an agreement on the basic facts."

That such a serious planetwide crisis has become a divide across the American political battlefield "is a tragedy" to Peter Kalmus, an earth scientist with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech in Pasadena, who agreed to be interviewed for this story on his own behalf (not on behalf of NASA, JPL or Caltech).

Kalmus warns that climate change is happening whether politicians want to talk about it or not.

"CO2 molecules and infrared photons don't give a crap about politics, whether you're liberal or conservative, Republican or Democrat or anything else," Kalmus said.

Slowing climate change will be essential, since adapting to all its impacts may be impossible. Governments must strive for greater resource efficiency, shift to renewable energy and transition from conventional to more sustainable agricultural practices.

America's leaders must also implement a carbon pricing system, climate activists say, that places a financial burden on fossil fuel producers and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. But there may be little to zero hope that such a system will be installed at the federal level as Trump prepares to move into the White House. Trump has actually threatened to reverse any commitments the United States agreed to in Paris. According to widely circulating reports, Trump has even selected a well-known skeptic of climate change, Myron Ebell, to head his U.S. Environmental Protection Agency transition team. Ebell is the director of the Center for Energy and Environment at the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

Steve Valk, communications director for the Citizens' Climate Lobby, says the results of the presidential election come as a discouraging setback in the campaign to slow emissions and global warming.

"There's no doubt that the steep hill we've been climbing just became a sheer cliff," he said. "But cliffs are scalable."

Valk says the American public must demand that Congress implement carbon pricing. He says the government is not likely to face and attack climate change unless voters force them to.

"The solution is going to have to come from the people," he said. "Our politicians have shown that they're just not ready to implement a solution on their own."

After Paris

There is no question the Earth is warming rapidly, and already this upward temperature trend is having impacts. It is disrupting agriculture. Glacial water sources are vanishing. Storms and droughts are becoming more severe. Altered winds and ocean currents are impacting marine ecosystems. So is ocean acidification, another outcome of carbon dioxide emissions. The sea is rising and eventually will swamp large coastal regions and islands. As many as 200 million people could be displaced by 2050. For several years in a row now, each year has been warmer than any year prior in recorded temperature records, and by 2100 it may be too hot for people to permanently live in the Persian Gulf.

World leaders and climate activists made groundbreaking progress toward slowing these effects at the Paris climate conference. Here, leaders from 195 countries drafted a plan of action to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and steer the planet off its predicted course of warming. The pact, which addresses energy, transportation, industries and agriculture — and which asks leaders to regularly upgrade their climate policies — is intended to keep the planet from warming by 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit between pre-industrial years and the end of this century. Scientists have forecast that an average global increase of 3.6 F will have devastating consequences for humanity.

The United States pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 26 percent from 2005 levels within a decade. China, Japan and nations of the European Union made similar promises. More recently, almost 200 nations agreed to phase out hydrofluorocarbons, extremely potent but short-lived greenhouse gases emitted by refrigerators and air conditioners, and reduce the emissions from the shipping and aviation industries.

But in the wake of such promising international progress, and as 2016 draws to a close as the third record warm year in a row, many climate activists are disconcerted both by United States leaders' recent silence on the issue and by the outcome of the presidential election. Mark Sabbatini, editor of the newspaper Icepeople in Svalbard, Norway, believes shortsighted political scheming has pushed climate change action to the back burner. He wants to see politicians start listening to scientists.

"But industry folks donate money and scientists get shoved aside in the interest of profits and re-election," said Sabbatini, who recently had to evacuate his apartment as unprecedented temperatures thawed out the entire region's permafrost, threatening to collapse buildings.

Short-term goals and immediate financial concerns distract leaders from making meaningful policy advances on climate.

"In Congress, they look two years ahead," Sabbatini said. "In the Senate, they look six years ahead. In the White House, they look four years ahead."

The 300 nationwide chapters of the Citizens' Climate Lobby are calling on local governments and chambers of commerce across America to voice support for a revenue-neutral carbon fee. The hope is that leaders in Congress will hear the demands of the people. This carbon fee would impose a charge on producers of oil, natural gas and coal. As a direct result, all products and services that depend on or directly utilize those fossil fuels would cost more for consumers, who would be incentivized to buy less. Food shipped in from far away would cost more than locally grown alternatives. Gas for heating, electricity generated by oil and coal, and driving a car would become more expensive.

"Bicycling would become more attractive, and so would electric cars and home appliances that use less energy," said Kalmus, an advocate of the revenue-neutral carbon fee.

Promoting this fee system is essentially the Citizens' Climate Lobby's entire focus.

"This would be the most important step we take toward addressing climate change," Valk said.

By the carbon fee system, the revenue from fossil fuel producers would be evenly distributed by the collecting agencies among the public, perhaps via a tax credit. Recycling the dividends back into society would make it a fair system, Valk explains, since poorer people, who tend to use less energy than wealthier people to begin with and are therefore less to blame for climate change, would come out ahead.

The system would also place a tariff on incoming goods from nations without a carbon fee. This would keep American industries from moving overseas and maybe even prompt other nations to set their own price on carbon.

But there's a problem with the revenue-neutral carbon fee, according to other climate activists: It doesn't support social programs that may be aimed at reducing society's carbon footprint.

"It will put no money into programs that serve disadvantaged communities who, for example, might not be able to afford weatherizing their home and lowering their energy bill, or afford an electric vehicle or a solar panel," said Renata Brillinger, executive director of the California Climate and Agriculture Network. "It doesn't give anything to public schools for making the buildings more energy efficient, and it wouldn't give any money to farmers' incentive programs for soil building."

Brillinger's organization is advocating for farmers to adopt practices that actively draw carbon out of the atmosphere, like planting trees and maintaining ground cover to prevent erosion. Funding, she says, is needed to support such farmers, who may go through transitional periods of reduced yields and increased costs. California's cap-and-trade system sets up an ample revenue stream for this purpose that a revenue-neutral system does not, according to Brillinger.

But Valk says establishing a carbon pricing system must take into account the notorious reluctance of conservatives in Congress.

"You aren't going to get a single Republican in Congress to support legislation unless it's revenue-neutral," he said. "Any policy is useless if you can't pass it in Congress."