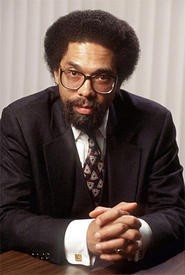

West, the public intellectual and widely cited authority on American race relations, now famous for playing himself in the last two Matrix movies, calls everybody "brother" or "sister." It's so very '60s and Christian and gentlemanly of him. For example, he and "Brother Prince" wrote Never Forget's first single, "Dear Mr. Man."

Prince surprised fans with last month's protest LP Planet Earth, and now this? Since when has he been down with the cause?

"I went to Paisley Park some years ago," explains West. "[Prince] has those xenophobia conferences every year. He brings in people from all around the world. He pays for it, actually. They're there for three days. There's dialogue during the day on all the various forms of xenophobia. I gave a lecture. And then that night, I remember seeing Norah Jones before she was big. Of course, Sheila [E.] was there. Maceo [Parker] was there. Chaka Khan was there . . . "

"Dear Mr. Man," an organ-goosed open letter to the U.S. government -- in which most of West's contributions consist of ad-libs like "Break it down, Brother Prince!" -- finds the Purple One railing against environmental abuses, constitutional abuses, Geneva Convention abuses, and institutional racism.

Other tracks on Never Forget, like "Mr. President" (featuring KRS-One and M1), tout similar sentiments. But not all of the fire and brimstone is directed at the White House. West also calls out his rap-artist brothers and sisters for "degradin' other folk."

"50 Cent, Snoop, Game, Nelly," says West, as if he's writing their names on the board. "On one level, I love those brothers because their artistic and aesthetic work is a part of who I am. On the other hand, I challenge those brothers because I'm just against misogyny. I'm against homophobia . . . I just have to take a stand against that. It's just who I am. Now that's a little different from this post-Imus trashing of Snoop. Because I'm not part of that crowd at all."

West bridges the generation gap by including guests from Lenny Williams and Gerald Levert (before his death late last year) to Andre 3000 and Rhymefest. Though Never Forget is hip-hop heavy, West doesn't consider himself a part of the hip-hop generation. He calls himself a "Motown-Philly Sound-Curtis Mayfield-generation brother" who "intervenes in the culture of young people."

"It's a matter of trying to present to young people a danceable education," he says. "Or what I call a 'singing paideia.' [Paideia means "a deep education" in Greek.] You have to get people's attention and focus on serious issues. Then you try to cultivate their self and put a premium on critical reflection, and then you try and engage in the maturation of the soul, which has to do with courage, compassion, and just love."

That's what's happening on "The N Word," the Never Forget dialogue with Georgetown University Professor Michael Eric Dyson. It's a sequel to a song of the same name on West's 2001 CD, Sketches of My Culture, in which he calls on black folk and rap artists to stop using the word "nigga."

In April of this year, Russell Simmons and other record-industry leaders called for a moratorium on the word in hip-hop records. Many argue that in the last half-century, "nigga" has been appropriated by blacks as a term of endearment among themselves. The 2007 version of "The N Word" continues the debate while a flutist ("an Italian brother, Brother Dino") darts in and out of West and Dyson's statements over a James Brown-ish vamp, just as Brian Jackson would with Gil Scott-Heron.

West believes that the pejorative "nigger" can't ever be completely separated from the hip-hop-friendly "nigga." But if he can't get people to stop using it, he hopes they at least become more aware of how, even with the best intentions, the word can become dangerously misunderstood.

"There is a rhythmic seduction with the word," says West. "If you want to say 'cat' or 'companion' or 'comrade,' that doesn't have the same rhythmic resonance as the word 'nigga.'

"The rhythmic seduction goes hand in hand with how black people use language. You're just not going to get folks to stop using words like that. It just ain't gon' happen. The question is, when these young people use 'nigga' with an 'a,' are there elements of self-hatred -- dishonoring each other, disrespecting, distrusting each other -- which is part of the history of the word with an 'er'?

"It's really about 'Show me the love and the respect and the honor and the dignity, and you can basically use any word you want.' But if I see these young folk using 'nigga' with an 'a,' and they still disrespecting one another, dishonoring one another, mistreating one another, and player-hating one another -- then I know the effect of the 'er' word is still operating in the 'a' word."