Special is the act that survives the chrysalis to emerge as a new entity: the Flaming Lips' transformation from psychedelic freaks to symphonic pop composers, Radiohead's leap from dyspeptic guitar rock to cinematic sound sculptures.

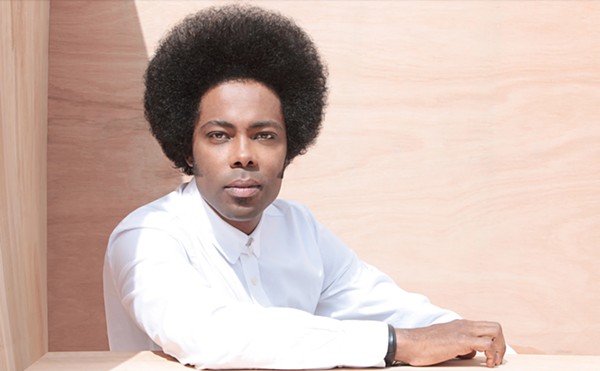

With its latest release, 23, Blonde Redhead makes the case that it belongs alongside such esteemed company. Over the past seven years, the New York trio's sound has completed a metamorphosis from cacophonous, no wave-inspired art rock to agile, atmospheric pop.

Though the transition has alienated many fans, its culmination, the cryptically titled 23, entrances with a wispy, textural lope that's dotted with passing swells of tart reverb and undulating background noise.

The band formed in New York City in 1993 when Italian twins Amedeo and Simone Pace, who were both studying jazz, met Kazu Makino and Maki Takahashi, art students from Japan. The foursome started a band and soon caught the ear of Sonic Youth drummer Steve Shelley, who agreed to produce the band's debut and release it on his imprint, Smells Like Records.

Takahashi left after the album's release, but the band forged ahead as a trio, bringing in the occasional guest bassist, including Unwound's Vern Rumsey and the Sugarcubes' Skùli Sverrisson.

Blonde Redhead's three subsequent releases -- La Mia Vita Violenta, Fake Can Be Just as Good, and In an Expression of the Inexpressible -- built upon the group's disjunctive rumble. These discs bristled with dynamic energy, chaotically zigzagging from minimalist peals to lo-fi tsunamis spiked with ragged distortion. Makino's high-pitched squeal, often resembling Shonen Knife spending the night in Eli Roth's Hostel, accompanied her band's terse, wiry ruckus.

Whether it was the Shelley connection or the group's failure to differentiate itself enough from its influences, Blonde Redhead was second-shelf post-rock -- Sonic Youth sidekicks, sitting underneath prime noise rockers like Unwound, the Melvins, and Shellac.

Mistaken for hipster-come-latelys, Blonde Redhead signaled a change with 2000's Melody of Certain Damaged Lemons. Boasting a lighter touch, delicate tracks like the sparse "Hated Because of Great Qualities" and the aching "For the Damaged" demonstrated unseen depth and craft. The discordant, anxious arrangements lift like fog, revealing less threatening textures and what sound like songs instead of exercises.

Although the austerity of Melody somewhat prepared listeners for what was to come, Blonde Redhead's next album, 2004's Misery Is a Butterfly, still caught many totally off guard.

Perhaps some of the shock can be attributed to the four-year gap between releases. Blonde Redhead seemingly fell off the face of the planet -- and for good reason. Besides eviction from several rehearsal spaces, as well as the typical label hassles, singer and guitarist Makino nearly died when she fell from a horse, shattering her jaw. After that she suffered a bout of pneumonia, further setting back the making of Misery.

The events were traumatic on a level that transcends band relations: Makino isn't just a fellow guitarist; she's Amedeo's mate.

Of course, during the same period, New York was undergoing its own horror. But despite all the tension, Misery Is a Butterfly is gentle, ethereal pop -- smooth and transparent as watercolors. Producer Alan Moulder (Smashing Pumpkins, My Bloody Valentine) generates a warmth capable of melting marshmallows. Quirky tracks like "Top Ranking" even suggest baroque pop mavens St. Vincent or Feist.

Yet Blonde Redhead balances pop glimmer with some taut elements: the steely guitars on "The Dress," the odd flute-like harmonics on the fringes of "Heroine." These prevent the music from floating away.

Makino actually sings; her thin, girlish voice slithers through the ripe, dulcet arrangements. Strings gild many tracks, while a brightness makes the entire album shimmer.

According to Amedeo, Blonde Redhead wanted to work with strings since their debut album, but Misery was the first time it actually worked out. The band -- with no label to answer to after leaving Touch & Go -- recorded the disc on its dime. It was a finished product long before 4AD signed them.

The reason for the record's sunny sounds may have been the band's sudden awareness of life's uncertanties after Makino's accident. Brushing abruptly against life's tenuous felicity, Blonde Redhead decided to swathe themselves in a more fragile sound. Beauty became not something to fuck with, but something to embrace.

Makino hinted as much in a Magnet interview several years back. "I started to look at a butterfly and saw it as something miserable. I felt the burden of being a butterfly," she said, looking back on her ordeal.

Whatever the impetus, the band's entire emotional thrust changed, as did its melodic timbre. And indie fans took note: The band reached a new level of popularity.

Then again, in light of 23's vibrancy and effortlessness, Misery now comes off as a crucial if at times rocky transition.

With an arch but elegant beauty, 23 also subscribes to an otherworldliness that prevents it from becoming too airtight. The title track surfs a coursing drone worthy of the Reid brothers, while the billowing, keyboard-driven "Sw" emerges from a neo-psych haze to almost run over Sgt. Pepper's horn section during the break. It certainly boasts the most expansive sonic scope of any Blonde Redhead release to date.

The reason there generally aren't second acts in America, to paraphrase F. Scott Fitzgerald, is that most don't have enough material to make it out of the first scene. Blonde Redhead, however, has stepped out from underneath Sonic Youth's shadow, forging a new sound by dint of near-heartache.

They've demonstrated enough craft to go from stinging post-rock to rolling, cotton-candy textures obscuring supple intensity. If 23 is any indication, this second act could last for a while.