So is Monsieur Ibrahim Omar-worthy? Sort of. Lighthearted, light-handed (except for the Biblical symbolism of the character names), the film dances into a world where every loss of innocence is backed by groovy music and glamorous, motherly prostitutes are a boy's best friends. Abandoned by his real mother long ago, now left adrift by his father's spiraling depression, Moses (Pierre Boulanger) turns 16 with no guidance and practically no acknowledgment. Determined to relieve himself of his virginity, he breaks his childhood piggy bank, exchanges the coins for cash at the corner grocery store, and persuades a buxom blonde (his second choice among the women on the strip) to initiate him.

Then he returns to his apartment and does a little dance. The morose walls and towering bookshelves, loaded with Hebrew texts, may legislate solemnity, but Moses is determined to enjoy himself. When his father (Gilbert Melki) storms into the kitchen and shuts off the radio, Moses simply turns it back on. When his father begs for the bathroom (his laxative having kicked in), Moses dawdles inside, keeping the door locked, enjoying his father's urgency. There's some serious life-juice flowing through this kid's veins, and he's not about to let it die.

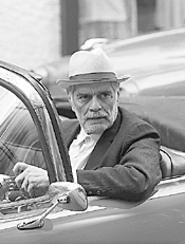

Still, Moses is alone, even more so as the film progresses. Like a baby adrift on a river, he has lost his moorings; one family has effectively surrendered him, and another has yet to discover him. Enter Monsieur Ibrahim (Sharif), the grocery-store proprietor, who perches darkly behind the counter and eyes Moses's petty thefts with silent forbearance. Moses's father refers to the man as an "Arab", but, Moses soon learns, Ibrahim is a Muslim from the Fertile Crescent, whatever that is. (Moses has to look it up.) Before long, the boy and the man are friends, with Ibrahim supplying not merely dinner, but an endless stream of life lessons, gleaned from a wackily personal translation of the Koran via Sufism and, one imagines, a few other things.

It's these life lessons that sap the movie of some of its energy; they're just a bit too self-conscious -- and too frequent -- to be tolerable. The Biblical Abraham may have been the consummate father (and the father, interestingly, of the Jewish people), and he did have a direct line to God, but even he must have had the modicum of grace required to keep some of his advice to himself. (Anyway, a personal relationship with God doesn't necessarily convey trust. Remember the thing with Isaac and the altar? Thank God for that ram.) At any rate, Sharif wears his wisdom in his craggy face; adaptor-director François Dupeyron might have trusted him to act from this knowing place, rather than talking about it ad nauseam.

Ibrahim does have some worthy things to say ("Slowness: That's the key to happiness"), but he's never more fun than when he's contradicting himself. (First he tells Moses to smile more; then, when the smiling doesn't quite work, he tells him to stop smiling.) At least in these moments, it's clear that Ibrahim is full of it; we're meant to enjoy his attempt to be wisely eccentric, or eccentrically wise, rather than listening to any particular thing that issues from his mouth. Anyway, the point of Ibrahim's character is not what he says, but what he does: He takes Moses into his heart and holds him there, giving him exactly what he needs -- i.e., a loving father. Meanwhile, Ibrahim's own heart could use some holding, and that's what it gets.

By the end, Monsieur Ibrahim's determination to be lighthearted in the face of tragedy is a little wearying. A final accident goes down a little too easily for this reviewer's tastes; or maybe it's that the film, having tried so hard to deny gravity, can't now accommodate it. Whatever the case, the result feels forced, and the closing scenes wrap up the package with far too tight a bow.

Meanwhile, Dupeyron is too taken with his soundtrack for his film's good. Yes, the music is fabulous ("Wooly Bully," anyone?), but must we feel inclined to shake our hips every single time Moses sallies forth on the streets of Paris? The optimism of the early '60s was doubtless a powerful force, but even Bill Haley and the Comets would have had to stop rockin' around the clock at some point -- particularly, one imagines, if they had been confronted with such a series of critical abandonments.