As the economies of two great Midwestern cities cratered, Dan Gilbert emerged not just unscathed, but stronger, richer, more powerful. At the center of the billionaire's empire, of course, is Quicken Loans, the company he founded that has risen from the ashes of the 2007 housing market collapse.

The tentacles of Gilbert's riches reach out across the Rust Belt in veins that touch just about every sector of the economy, as you're well aware. In Cleveland, he has the Cavs, newly anointed the next champions of the NBA after Gilbert's wooing of LeBron back to the shores of Lake Erie. And the Horseshoe Casino, and Bizdom U, and a 300-person-plus downtown office of Quicken Loans, headquartered in Detroit.

Back in Michigan, where the 52-year-old makes his home in the Oakland County village of Franklin, his influence is far greater. Gilbert has ushered in a remarkable turnaround for Detroit's quiet downtown, buying some 60 buildings bustling with some 12,000 employees, more than 2,500 of whom are residents of Detroit proper, feeding much needed income tax into the coffers of the bankrupt city of 680,000. The Detroit metro area is also home to dozens of other companies Gilbert has a stake in, including Bedrock Real Estate Services, Fathead and the Greektown Casino.

The national spotlight has shone warmly on Gilbert's investments, especially in Detroit where sentiments root for a municipal nightmare of an underdog to undergo the sort of turnaround of which everyone dreams. Politics, for example, have appeared to make that an easy call: Thanks to Michigan's Democratic then-governor Jennifer Granholm, the state and city agreed to cough up to $200 million in tax incentives over two decades to woo Gilbert's enterprise. Though many forget, Gilbert dangled the prospect of moving Quicken HQ to Cleveland, before conceding to the Plain Dealer that it's "awfully hard to move 3,500 people."

Yet rarely do we see a glimpse of skepticism, of worry that Gilbert is less savior than rat real estate king, of concern whether what's good for Gilbert is really good for Cleveland or Detroit.

Questioning Gilbert's good intentions was a point writer Mark Binelli raised in the New York Times back in February 2013, before Michigan appointed an emergency manager in Detroit and officials buckled and filed for municipal bankruptcy.

"Detroiters who are worried about ceding local power to Michigan's Republican governor shouldn't forget the ways in which power has already been ceded to an unelected oligarchy, whose members might, no matter how ostensibly well intentioned, possess questionable ideas about urban renewal," Binelli wrote.

There's no question Gilbert's profile has risen due to his successful efforts in bringing businesses into downtown. But it also has been aided and abetted by an adoring public, one who wants to see Detroit thrive like it did when the auto industry still reigned, seemingly by any means necessary, and one in Cleveland who shouts rah-rahs from every street corner at any semblance of downtown development, even if it is a casino.

With such a widespread presence, it becomes easier to see why some have wondered aloud if local media outlets themselves can maintain a healthy level of skepticism of Gilbert's efforts. Writing for the Columbia Journalism Review, Anna Clark noted that "local coverage [in Detroit] of Gilbert reveals some solidly informative reporting, some glaring gaps, and the occasional cringe-worthy moment."

One of those glaring gaps, for instance, is what connection Quicken had with the housing crisis of 2007. When questions have been raised, the company has vehemently downplayed any role, bristling at any slight possibility that Quicken's well-respected name could take a hit.

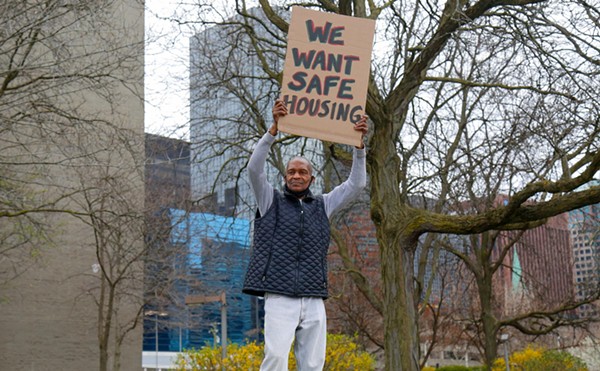

Gilbert pushes back against any allegation by painting Quicken as one of the good guys of the industry, a lender that didn't dabble in the type of risky loans and bad practices that eventually generated economic catastrophe, especially in Cleveland and Detroit. Ohio in total had some 100,000 vacant properties in 2013, with 26,000 in Cuyahoga County and 16,000 in Cleveland. The 2013 rate of 9.5 percent of Northeast Ohioans 90 days delinquent or in foreclosure was among the highest in the country.

In the wake of the industry's implosion, Quicken emerged unscarred. Since the mortgage crisis dissipated, Gilbert has amassed an even larger fortune and the biggest stake — and subsequently, clout — in the direction of how Detroit and Cleveland seek to rebuild.

While doing so, the notion that Quicken escaped the foreclosure crisis without any stains on the company's record has been virtually accepted by the public.

Reports and profiles of Gilbert attribute Quicken's escape from the economic collapse to business: that it was a lender who only commingled with safe practices and products.

But lawsuits, federal settlements and records, and interviews with experts suggest a conflicting perspective: It's not that Quicken wasn't hurt by the foreclosure crisis because it avoided risky loans; it wasn't hurt because it passed the risk off to others as soon as the loans were made.

The Gilbert Reaction

First, a note on how Dan Gilbert reacts to media criticism:

Back in early September, Plain Dealer sports columnist Bill Livingston was a guest on Tony Kornheiser's radio show in Washington D.C. on ESPN 980. In the midst of a wide-ranging conversation on Cleveland sports — Johnny Manziel! LeBron's coming back! — the topic of Dan Gilbert came up and Livingston didn't hold back his feelings while touching on Gilbert's infamous letter and more.

"I could understand playing to his base," Livingston said. "But this is not the first time that he had released statements like this that weren't pretty... They were sent out late at night, and draw some connotations from that if you will."

He continued, leaving the vagaries behind.

"He can have a bit of a hair trigger," he said. "He can become influenced by all the things that a late night would engender. I think probably alcohol probably played a part of it, just to come out with it. It's just suppositional on my part, but he's sent out messages like this before, to Plain Dealer people on the casino issue, that were over the top."

Livingston was speaking the truth, as three media sources have told Scene over the years, describing similar interactions with Gilbert and worse. The billionaire can unleash torrents of spite when reporters question his decisions, and this time he went straight to Livingston's bosses at the Plain Dealer with his complaints. They, in turn, would tell Livingston to write a letter of apology to Gilbert, a sanctioned snipping of one of the few who dare call Gilbert to the carpet.

Touchy on the Cavs, and as Livingston said, touchy on the casino.

Back in 2009, Gilbert scammed Ohioans into voting for one of the most lopsided casino deals in the country. A central tenant of Gilbert's proposal was a $600 million casino overlooking the Cuyahoga River. Once the keys that unlocked the gate to the glorious forest of never-ending money trees were handed over, Gilbert announced the Horseshoe Casino in Cleveland would be housed in the old Higbee Building, with phase 2, the one promised to voters, coming later down the line.

Five years later, phase 2 is exactly where it was then.

The Northeast Ohio Media Group's Brent Larkin penned a September 2014 column calling out Gilbert's failure to complete phase 2 yet again, and the numbers were startling and Larkin's sword sharp. The voter push promised 34,000 jobs. The reality: 10,600 temporary jobs and 4,844 full time.

"Just days before hoodwinking voters in 2009," Larkin wrote, "Gilbert sent vile emails to top Plain Dealer executives after the newspaper ran a legitimate story reporting Gilbert had been arrested on gambling charges while a student at Michigan State University.

"In May 2013, [Gilbert] tweeted that I was a yellow journalist for having the audacity to suggest he hadn't kept his word to voters, adding 'more to be revealed in the months ahead' about the new casino.

"Seventeen of those months later, we're still waiting.

"Instead of details about that new casino, we've gotten a proposed park with a cheesy sculpture on a postage-stamp-sized parcel of land near Gilbert's downtown casino."

That is a side of Daniel Gilbert, founder of online lending giant Quicken Loans, the public doesn't hear about too often.

The full-throttled response from Dan Gilbert isn't a surprise, however, to one employee of Quicken Loans. As he put it, it's clear Quicken employs a clipping service to keep tabs on media reports about the company. And there have been concerns about employees speaking with media outlets.

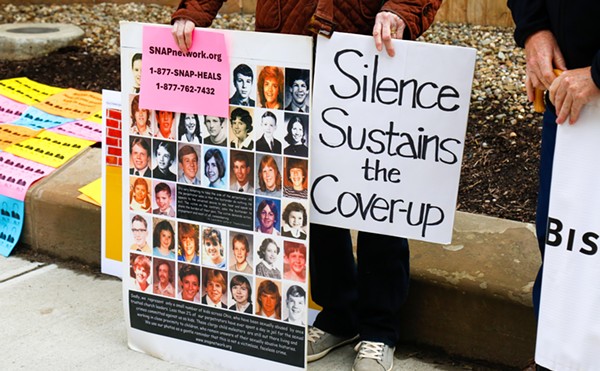

After a colleague appeared in a report on the Albert — a Detroit-area redevelopment of luxury lofts that resulted in the displacement of a number of low-income residents — "with a fair and, admittedly, dissenting opinion," a company meeting was called to discuss media relations, the employee told Scene.

In essence, the employee says, the thrust of the meeting was that "when speaking to media ... try to not necessarily shed a poor light on the progress that's being made."

"It certainly was interesting that a week after the piece was published that all of the sudden we're all being just reminded about appropriate action when speaking with the media," the employee says.

Employees "more or less" were encouraged to direct questions to Quicken's public relations department.

"It certainly was not a gag order," he says, "but it was a friendly reminder."

Another current employee who declined to be named says that Quicken as a whole is very touchy about news coverage and actively seeks out the identities of those who speak to the media anonymously — characterizing the process as a "very diligent" hunt to out those who talk.

That concern runs up the chain. When Scene made exploratory phone calls to employees on a Quicken story unrelated to the housing crisis, it received an unprompted email from Tad Carper, VP of communications for the Cleveland Cavaliers, asking what the Quicken story was all about.

That sensitivity has deep roots: In 2008, Crain's delivered an expose on a convoluted lawsuit involving Quicken-financed mortgages. The company contended a borrower had conspired to fraudulently purchase 16 homes through transactions with Quicken. However, Clark wrote in the Columbia Journalism Review, "Crain's saw the lender as part of a culture of 'easy money, rushed deals.'"

At the time, Gilbert was incredulous.

"Crain's came to these intellectually impotent conclusions over 16 loans where we are the plaintiff suing for fraud," Gilbert wrote in a response letter to Crain's. "The other approximately 400,000 loans we closed in all 50 states over the past eight years avoiding fraud, subprime and other short-sighted mortgage fads of the last decade somehow went unaccounted for in the articles."

Three years later, real estate reporter Michael Hudson of the Center for Public Integrity (CPI) took a deep dive into Quicken's record. To some, Hudson found, Quicken had in fact hopped the bandwagon on some of those mortgage fads. Between lawsuits from employees who painted a work culture unlike the one Gilbert portrays to the public, and cases involving borrowers who contended they were given a raw deal from Quicken, Hudson wrote those "claims are at odds with [Quicken's] squeaky clean image."

No local media followed Hudson's lead. When a reporter from CBS News asked Quicken for comment on the story, the company jumped to extremes. A spokesperson immediately sought to discredit Hudson, who has covered the finance industry for over two decades, and his outlet as a "not very credible source."

Nearly four years after the report was published, Gilbert contends that the Center for Public Integrity is "biased against us." During an interview, he provides a nine-page, daunting point-by-point rebuttal that was seemingly shared with local media outlets at the time Hudson's report was published.

Clearly the years-old perceived offense is still on his mind.

A tour of the (mostly) familiar

Quicken has some notable marks on its lending record: There's a $6.5 million settlement the company reached in 2009 with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. over loans it sold to the now-defunct IndyBank that turned sour. Quicken assumed no liability or wrongdoing.

There also remain a number of active lawsuits, which accuse the company of lessening its underwriting standards for loans when times were good. In particular, one case shows, at the very least, one homeowner in Detroit foreclosed on his home after receiving a loan from Quicken in 2006. It was a particular product that has earned the ire of consumer advocates and lawmakers in light of the housing industry's implosion.

What's interesting about the allegations, now seven years removed from the height of the crash, is Gilbert's insistence that Quicken exclusively slung quality product.

In a recent interview with Forbes (where he mused that "debt is what's going to kill you"), Gilbert said that Quicken avoided risky loan products and subprime borrowers.

To the casual observer, it would appear that those aforementioned circumstances conflict with the presentation of the company Gilbert has portrayed to the public. It seemed prudent to reach out to Quicken to ask for some face-to-face time with Gilbert on the company's relationship with the lending industry during the boom years — especially considering the impact it had on the nation.

'We just did not do them'

Dan Gilbert's 10th floor office in the Compuware building is within earshot of other employees, which you might not expect. Inside, there's a cut-out of his face leaning on one wall.

Opening conversation hinges on the friendly topics of favorite beer, Gilbert's idol, and his time, very early in his life, as a TV reporter.

He laughs. "You really did your research," then adds that he can't recall a reporter ever asking him about that time in his life. Gilbert had a sports show on a cable station at Michigan State University, where he graduated with a degree in telecommunications.

Eventually, he spent four months working for WKZO-TV in Kalamazoo, covering day-to-day news. He shared camera duties with a partner who would also read the news. He soon realized he didn't have the interest in pursuing a career as a reporter

"I just realized, I don't know, it just probably wasn't my thing," he says.

He reflects on the answer, and adds that he hasn't seen any footage in about five years. "I have to figure out where it is," he says, with a light laugh.

There's a mantra Gilbert reiterates when asked about what the company is doing in Detroit: "Do well by doing good." What's that about?'

"I think there's a belief, and maybe rightfully so, about how certain companies and corporations have behaved over the years," he says.

He uses that phrase to explain that, in fact, some companies are not merely "profit based." There are some that are also "mission based."

"We also don't believe there's conflict in that," he says. "There are a lot of people who believe there's a conflict in that — if you make profit it has to be bad."

That's not the case with Quicken, he says. Since the company moved to Detroit, it boosts morale and makes employees feel like they're not solely coming to work for a profit-making business. There's more at stake here.

"So that's the general way we look at it," he says. "You can do both ... in our case, we obviously picked up a lot of property that was very low priced and I'm sure we wouldn't plan on selling it for years, not decades, if ever."

He continues: "And I'm sure there's a built-in gain there, but ... for us, it was, let's get in, let's help these buildings and let's make it happen. And we just believe — one of our 'isms,' as hokey as it is, is 'money follows' — there's not necessarily a conflict in that."

Gilbert occasionally hits the table to emphasize points. At 5-foot-6, he carries a commanding presence into the room, answering questions with ease. He's wearing a brown-ish fleece and his hair is slicked back, like it looks in every photo of Gilbert.

"Isms," for the uninitiated, are Gilbert's 19 corporate mantras that are defined in a thick book given to every employee and seen throughout the workspaces of every company in the Quicken family. Examples: "There is no they." (Everyone is in this together.) "We eat our own dog food." (Employees should be the biggest fan of Quicken.)

Back to his point, Gilbert says, "There's clearly a conflict in people who do things they shouldn't be doing."

Which brings us to the central question: Why does he maintain Quicken never slung rotten loans? The company avoided it, he maintains.

Quicken could have sold those loans, Gilbert says, "But that doesn't matter. We're [still] collectible. We have reps and warranties on all these loans. They can come back to us. So we didn't do them. We just did not do them."

The issue at hand with the $6.5 million FDIC settlement relates to the so-called representations and warranties Gilbert alludes to. That refers to reference language included in any sale of loans that allows the purchaser to find loans that don't meet standards, and then require the originator to buy them back. The FDIC declined to comment about the settlement, citing agency policy.

But while Quicken may have been liable, the buy-back period was limited to a finite time span, typically up to one year, says Steve Dibert, founder of mortgage fraud investigation company MFI-Miami. After that, the repercussions of potentially shoddy loans were left to the purchaser. And if an auditor ever reviewed the package of loans, they reviewed a fraction of a percent, Dibert says.

Back inside Gilbert's office: Even so, he says, the buy-back of loans due to breached representations and warranties is common in the lending industry He takes pains to stress that this is unrelated to problems that led to the mortgage industry's implosion of 2007. It is common.

When Quicken sells a loan into the secondary market, Gilbert says there's two instances where the company must represent and offer warranties on what it has sold. First, he says, there's borrower fraud.

That is, "the borrower commits fraud on that loan and we just didn't catch it for fraud, and then we sell that loan, and then later on it defaults and [the purchaser catches] fraud in the loan ... they can push that loan back to us," he says. "Some borrowers are pretty damn good at fraud."

Then, there's internal fraud, "which was almost never the case," says Gilbert. "There may have been a handful of loans.

"This is something that has gone on for 25 or 30 years," he says of repurchasing mortgages. "[T]here's X amount of loans ... [and] a small percentage goes bad, which, when you're doing a large volume, can be a lot of loans, the first thing [the purchaser wants] to do is ask, 'Can we push the loan back?'"

What generally happens then, Gilbert says, is a negotiation.

"These settlements happen all the time," he says, adding, "This [was] just a routine settlement. We probably settled more than $6.5 million in loans this month with investors."

There are those who say Quicken escaped any liability because they immediately sold the rights to nearly 90 percent of the loans the company originated during the housing boom years, 2005 to 2007.

The lending model that became the name of the game was this: Quantity over quality. At the turn of the century, it became more typical for loans to be bundled into a pool, sold to another lender, and then eventually sold again into a mortgage-backed security on Wall Street.

But Gilbert bristles, saying it's commonplace for loans to be sold into the secondary market.

"Except for a handful of banks that just keep a handful of their loans in portfolio, on their balance sheet, every other loan that's originated in the United States — whether from a bank, mortgage company, mortgage broker — is sold into the secondary market," he says. "That was true then, [and it's] true now."

Subprime confusion

On the surface, saying Quicken never messed with subprime lending is, at the very least, a confusing brand of definitive statement to make: A review of published reports during the height of the housing boom show a narrative that bounces back-and-forth from reiterating Gilbert's line that Quicken didn't dabble in subprime or risky loans to a completely contradictory picture.

In March 2007, for instance, Quicken CEO Bill Emerson spoke on CNN about the subprime mortgage industry and said 2 percent of the company's total lending business was in subprime loans.

Later that year, the Detroit News reported that, in 2006, Quicken sold the third-highest amount of subprime loans in Metro Detroit; however, that only accounted for just over 20 percent of its business that year.

In June 2008, News' financial columnist Brian O'Connor wrote that a pool of loans at the center of a legal dispute between Quicken and Wells Fargo included "subprime adjustable-rate mortgages to home equity lines of credit, [which] were sliced and diced so many ways, and passed around to so many buyers, that everyone claimed risk had been diversified right out of the system."

As Gilbert puts it, though, subprime lending comes down to a matter of how the word is defined. What it was in 2006 and what it is today is entirely different. To him, "subprime" means a borrower with a low credit score and a high loan-to-value ratio, which is a comparison between the amount of the loan to the value of a home.

He stresses this point. It's the one thing that "drives him crazy" — reports that question whether or not Quicken sold subprime.

"There's no set definition of what is subprime," Gilbert says. "The only thing that really is defined is conforming, Fannie, Freddie, FHA loans," he says, adding, "Everything else ... nonconforming, subprime, alternative lending, jumbo [loans] .... nobody's got a real definition."

Gilbert says that judging a loan applicant can be broken down into four categories: credit score, the home's appraised value, employment history and assets.

"That's it," he says, "The first two is what drives it. And if you got loans that are high LTV and bad credit, you're going to have problems.

"That to me is subprime."

Gilbert also highlights the company's ranking by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) as having the third lowest delinquency rating among lenders. Called the "compare ratio," it compares the number of delinquencies to the FHA's national average, meaning Quicken's FHA default rate is half the national average.

And on the subject of overtime lawsuits against Quicken (and, really, on most lawsuits the company considers meritless), Gilbert says, "When companies settle, they become co-conspirators, because they just feed the monster. We're not going to do that ... For us, I couldn't look at our people everyday and say we paid this."

After a fast-paced 75 minutes, Gilbert departs and directs any specific questions about lending claims to the remaining group of vice presidents on the rest of the day's schedule.

In a follow-up email, citing CEO Aaron Emerson's 2007 remarks on CNN, Scene asks if the company ever sold subprime loans, and how much of it constituted the company's total lending.

Emerson responded that the vast majority of the company's business over the years has been and is "straight vanilla, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and FHA home loans.

"[I]f you are using the word 'subprime' as is most commonly used in today's world, which refers to toxic loans with 12 percent, 13 percent, 14 percent or even higher interest rates that was responsible for the collapse of the U.S. mortgage market and even the U.S. economy: NO, QUICKEN LOANS NEVER PARTICIPATED NOR ORIGINATED THESE TYPES OF LOANS," he wrote.

He adds: "As far as the specific stories you cite ... the paragraphs above should give you full and satisfactory explanation, and if not then the reports were flat-out wrong."

Got that? This, in response to a question as to why the company's CEO himself told a national news outlet that a fraction of his company's business in the mid-2000s was in subprime loans.

What about this?

Okay, so maybe they skirted selling an abundant amount of subprime loans. But then why is a bank currently suing Quicken-originated loans it says the company misrepresented, omitted, or even committed "fraud in the loan origination process"?

"The reviews revealed that many of the mortgage loans did not possess the represented characteristics and safeguards at the time of the securitization," the complaint filed by Deutsche Bank National Trust Co. says. Essentially, securitization is the process of combining a pool of contractual debt, such as residential mortgages, and selling that pool to investors with mortgage payments as security.

"Instead, therefore, of receiving a pool of loans having the characteristics and quality represented by Quicken, the trust received a far riskier and less stable loan pool," the complaint continues.

Deutsche cites an instance where borrowers misrepresented their income to Quicken, whom the complaint says "failed to test the reasonableness of such income."

According to the complaint, one borrower stated he was a restaurant manager, with a monthly income of $10,000 on his application for a loan. As it turns out, the borrower's income tax statements showed he earned only $4,621 per month.

Records show the $171,000 loan in question was a 5-year, hybrid adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) rider, which initially allowed the borrower to make payments that didn't even cover the monthly 6.875 percent interest costs. It bears mentioning that, at any given time, the borrower was afforded the ability to pay a larger amount to pare down the principal.

Interestingly, after five years, the interest rate could begin to change, records show, with a cap at 11.875 percent. At that point, the borrower could have begun to make interest-only payments.

But the borrower never reached that point. The Detroit home in question was eventually lost to foreclosure in 2010, records show. Attempts to reach the homeowner were unsuccessful.

It has also been established that Quicken sold so-called "stated-income loans," which eventually earned the pejorative title of "liar loans," as a borrower would only be required to state how much they earned without any supporting documentation.

Asked about whether Quicken ever sold "stated-income" products, Mike Lyons, vice president for operations at Quicken, spoke generally on the company's past practices: The company had a number of backstops in place to verify a potential applicants' employment and income, he says.

For example, if an applicant stated they made a certain amount, a loan officer would have tested the "reasonableness" of that figure by comparing it to an independent salary tool, like Salary.com. Bob Walters, the company's chief economist, says it's no secret these products were widespread during the boom years, and adds that, during an application process a company employee would then verbally verify with the applicant's employer to confirm employment status.

Today, Quicken doesn't offer stated-income products. However, Walters says it offered many homeowners who earned part-time income from various jobs, or those who were self-employed, an opportunity to achieve the American Dream: their own home.

"There was a lot of people that were able to buy homes — immigrants, people who have multiple families under one roof, quite frankly, a lot of people working under the table ... [who were] not always getting these nice W-2s that you and I may get," Walters says. "Maybe they're self-employed."

He adds: "Income is one of the biggest reasons people have a challenging time qualifying. Not because they don't have enough: It's because they can't easily document it."

This group of top Quicken reps never gets around to discussing specifics on certain lawsuits mentioned in initial inquiries to the company, because it becomes evident early on that everyone in the room could speak only in generalities.

So in the same follow-up email to Emerson, Scene asks directly about the specific loan for the Detroit homeowner referenced in the Deutsche lawsuit. Emerson tells Scene to "keep in mind" that the company has sold more than two million loans, and for years has had stringent underwriting controls in place.

"However, when a national home lender closes more 2.1 million mortgages, one would always be able to find a handful of loans and situations — even with the most stringent controls in place — where something potentially went wrong," he writes.

And, he continues: "Clearly, it would be an unfair characterization that anything in our underwriting or loan processing systems is defective using a handful of loans (or even hundreds of loans or more) as evidence of such."

Would Emerson's response have been the same if we included the fact that the same lawsuit from Deutsche mentions a loan for a home in Washtenaw County, Mich., where the borrower allegedly represented he earned $13,500 per month? As it turns out, the borrower's bankruptcy documents filed after he received the loan show he only earned roughly $8,837 per month.

Or, perhaps Emerson's response would change if we had mentioned the lawsuit filed by a Romulus, Mich., woman who claimed her Quicken loan officer, one day before closing, increased her closing costs by roughly double — and then gave her an interest rate nearly 2 percentage points higher. The net effect? The homeowner's monthly cost shot up $850 dollars, or 73 percent, to $2,036 per month, court documents show. Still, the homeowner signed anyway, which is partly why her case was dismissed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Or perhaps his response would have changed if we had mentioned the 79-year-old retired woman on a fixed income we recently met who, seven years ago, was sold a 30-year mortgage from Quicken for a home that was already paid off. It required her to pay interest only, for the first decade.

She will be 102 when her mortgage is fully amortized.